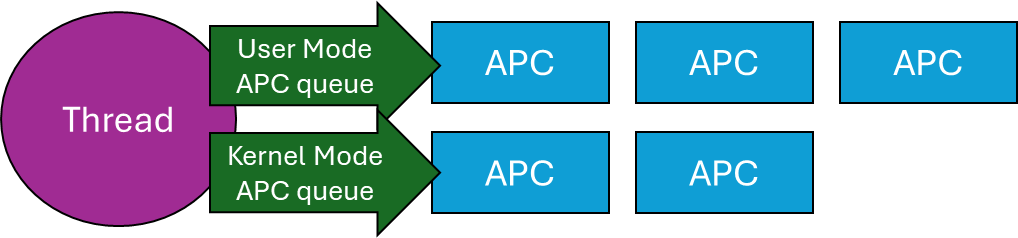

Asynchronous Procedure Calls (APCs) in Windows are objects that can be attached to threads. Every thread has its own APC queue, where an APC stores a function and arguments to call. The idea is that we’d like the a function to be executed by a specific thread, rather than some arbitrary thread. This is because the process this thread is part of is important for some reason, so the APC (when executed) has full access to that process resources.

Technically, there are user-mode, kernel-mode, and Special kernel-mode APCs, In this post I’ll discuss user mode APCs, those directly supported by the Windows API. (There is also Special user-mode APCs, but these are not generally usable). Here is a conceptual representation of a thread and its APC queues:

A Thread and its APC queues

When a user mode APC is queued to a thread (more on that later), the APC just sits there in the queue, doing nothing. To actually run the APCs currently attached to a thread, that thread must go into an alertable wait (also called alertable state). When in that state, any and all APCs in the thread’s queue execute in sequence. But how does a thread go into an alertable wait?

There are a few functions that can do that. The simplest is SleepEx, the extended Sleep function:

DWORD SleepEx(DWORD msec, BOOL alertable);

If alertable is FALSE, the function is identical to Sleep. Otherwise, the thread sleeps for the designated time (which can be zero), and if any APCs exits in its queue (or appear while it’s sleeping), will execute now, and the sleep is over, in which case the return value from SleepEx is WAIT_IO_COMPLETION rather than zero. A typical call might be SleepEx(0, TRUE) to force all queued APCs to run (if there are any). You can think of this call as a “garbage collection” of APCs. If a thread does not ever go into an alertable wait, any attached APCs will never execute.

Other ways of entering an alertable wait involve using the extended versions of the various wait functions, such as WaitForSingleObjectEx, WaitForMultipleObjectsEx, where an additional Boolean argument is accepted just like SleepEx. MsgWaitForMultipleObjectsEx can do that as well, although the alertable state is specified with a flag (MWMO_ALERTABLE) rather than a Boolean.

Now that know how user mode APCs work, we can try to put them to good use.

Asynchronous I/O Completion

The “classic” use of user mode APCs is to get notified of asynchronous I/O operations. Windows has several mechanisms for this purpose, one of which involves APCs. Specifically, the ReadFileEx and WriteFileEx APIs receive an extra parameter (compared to their non-Ex variants) that is a callback to be invoked when the asynchronous I/O operation completes. The catch is, that the callback is wrapped in an APC queued to the requesting thread, which means it can only execute if/when that thread enters an alertable wait. Here is some conceptual code:

HANDLE hFile = ::CreateFile(..., FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED, nullptr);

OVERLAPPED ov{};

ov.Offset = ...;

::ReadFileEx(hFile, buffer, size, &ov, OnIoCompleted);

// other work...

// from time to time, execute APCs:

::SleepEx(0, TRUE);

The Completion routine has the following prototype:

void OnIoCompletion(DWORD dwErrorCode,

DWORD dwNumberOfBytesTransfered,

LPOVERLAPPED lpOverlapped);

In practice, this mechanism of being notified of asynchronous /O completion is not very popular, because it’s usually inconvenient to use the same thread for completion. In fact, the thread might exit before the I/O completed. Still, it’s an option that utilizes APCs.

Injecting a DLL into a Process

It’s sometimes useful to “force” somehow another process to load a DLL you provide. The classic way of achieving that is by using the CreateRemoteThread API, where the “thread function” is set to the address of the LoadLibrary APS, because a thread’s function and LoadLibrary have the same prototype from a binary perspective – both accept a pointer. LoadLibrary is passed the path of the DLL to load. You can find a video I made to show this classic technique here: https://youtu.be/0jX9UoXYLa4. A full source code example is here: https://github.com/zodiacon/youtubecode/tree/main/Injection.

The problem with this approach is that it’s pretty visible – anti-malware kernel drivers get notified when a thread is created, and if created by a thread in a different process, that may be suspicious from the driver’s perspective. By the way, the “legitimate” usage of CreateRemoteThread is for a debugger to break in forcefully to a target process in an initial attach, by forcing a new thread in the process to call DbgBreakPoint.

Using an APC, we may be able to “persuade” an existing thread to load our DLL. This is much stealthier, since it’s an existing thread loading a DLL – a very common occurrence. To achieve that, we can use the generic QueueUserAPC API:

DWORD QueueUserAPC(

PAPCFUNC pfnAPC,

HANDLE hThread,

ULONG_PTR dwData

);

Fortunately, an APC function has the same binary layout as a thread function – again receiving some kind of pointer. The main issue with this technique is that the target thread may not get into an alertable wait ever. To increase the probability of success, we can queue the APC to all threads in the target process – we just need one to enter an alertable wait. This works well for processes like Explorer, which have so many threads it practically always works. Here is a link to a video I made to show this technique: https://youtu.be/RBCR9Gvp5BM

A Natural Queue

Lastly, since APCs are stored in a queue, we can create a “work queue” very naturally just by utilizing APCs. If you need a queue of functions to be invoked sequentially, you could manage them yourself with the help of (say) std::queue<> in C++. But that queue is not thread-safe, so you would have to properly protect it. If you’re using .NET, you may use ConcurrentQueue<> to help with synchronization, but you still would need to build some kind of loop to pop items, invoke them, etc. With APCs, this all becomes natural and pretty easy:

void WorkQueue(HANDLE hQuitEvent) {

while(::WaitForSingleObjectEx(hQuitEvent, INFINITE, TRUE) != WAIT_OBJECT_0)

;

}

Simplicity itself. An event object can be used to quit this infinite loop (SetEvent called from somewhere). The thread waits for APCs to appear in its queue, and runs them when they do, returning to waiting. Clients of this queue call QueueUserAPC to enqueue work items (callbacks) to that thread. That’s it – simple and elegant.

Summary

APCs provide a way to allow callbacks to be invoked sequentially by a target thread. Maybe you can find other creative use of APCs.