Millions of machines around the world crashed a few days ago, showing the dreaded “Blue Screen of Death” (BSOD), affecting banks, airports, hospitals, and many other businesses, all using the Windows OS and CrowdStrike’s Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) software. What was going on? How can such a calamity happen in one single swoop?

First, foul play was suspected – a cyber security attack perhaps. But it turned out to be a bad update of CrowdStrike’s “Falcon” software agent that caused all this mess. What is a BSOD anyway?

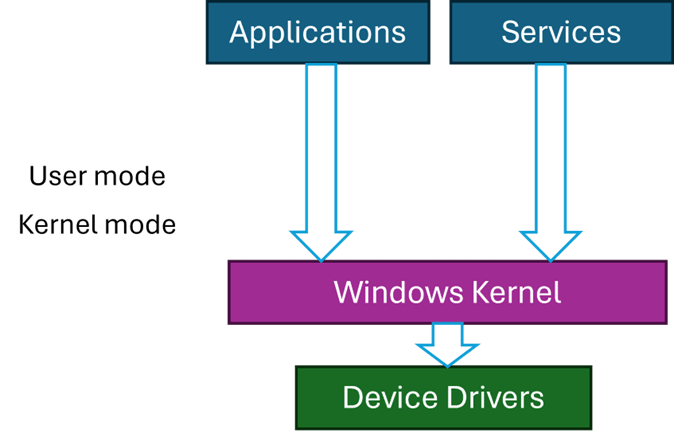

Code running on Windows can run in two primary modes – user mode and kernel mode. User mode is restricted in its access, which cannot harm the OS. This is the mode applications run with – such as Explorer, Word, Notepad, and any other application. Kernel mode, however, has (almost) unlimited power. But, as the American hero movies like to say, “With great power comes great responsibility” – and this is where things can go wrong.

Kernel code is trusted, by definition, because it can do anything. The Windows kernel is the main part of kernel space, but third-party components may be installed in the kernel, called device drivers. Classic device drivers are required to manage hardware devices – connecting them to the rest of the OS. The fact that you can move your cursor with the mouse, see something on the screen, hear game sounds, etc., means there are device drivers dealing with the hardware correctly, some of which are not written by Microsoft.

If a driver misbehaves, such as causing an exception to occur, the system crashes with the infamous BSOD. This is not some kind of punishment, but a protection mechanism. If a driver misbehaves (or any other kernel component), it is best to stop now, rather than letting the code continue execution which might cause more damage, like data corruption, and even prevent Windows from starting successfully.

Third party drivers are the only entities that Microsoft has no full control over. Drivers must be properly signed, but that only guarantees that they have not been tampered with, as it does not necessarily guarantee quality.

Most Windows systems have some Anti-virus or EDR software protecting them. By default, you get Windows Defender, but there are more powerful EDRs out there, CrowdStrike’s Falcon being one of the leaders in this space.

The “incident” involved a bad update that caused a BSOD when Windows restarted. Restarting again did not help, as a BSOD was showing immediately because of a bug in the driver when it’s loaded and initialized. The only recourse was to boot the system in Safe Mode, where only a minimal set of drivers is loaded, disable the problematic driver, and reboot again. Unfortunately, this has to be done manually on millions of machines.

The Windows kernel treats all kernel components in the same way, regardless of whether that component is from Microsoft or not. Any driver, no matter how insignificant, that causes an unhandled exception, will crash the system with a BSOD. Maybe it would be wise to somehow designate drivers as “important” or “not that important” so they may be treated differently in case of failure. But that is not how Windows works, and in any case, an anti-malware driver is likely to be tagged as “important”.

This entire incident certainly raises questions and concerns – a single point of failure has shown itself in full force. Perhaps a different approach to handling kernel components should be considered.

Personally, I was never comfortable with Windows uniform treatment of kernel components and drivers, but in practice it’s unclear what would be a good way to deal with such exceptions. One alternative is to write drivers in user mode, and many are written in this way, especially to handle relatively slow devices, like USB devices. This works well, but is not good enough for an EDR’s needs.

Perhaps specifically for anti-malware drivers, any unhandled exception should be treated differently by disabling the driver in some way. Not easy to do – the driver has typically registered with the kernel (e.g. PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineEx and others), its callbacks may be running right now – how would the kernel “disable” it safely. I don’t think there is a safe way to do that without significant changes in driver protocols. The best one case do (in theory) is issue a BSOD, but disable the offending driver automatically, so that the next restart will work, and a warning can be issued to the user.

This is not ideal, but is certainly better than the alternative experienced in the recent crash. Why is it not ideal? First, the system will be unprotected, unless some default (like Defender) would automatically take over. Second, it’s difficult to determine with 100% certainty that the driver causing the crash is the ultimate culprit. For example, another (buggy) driver may write to anywhere in kernel space, including memory that may belong to our anti-malware driver, and that write operation does not cause an immediate crash since the memory is valid. Later, our driver will stumble upon the bad data and crash. Even so, some kind of mechanism to prevent the widespread crash must be set in place.