It’s been a long while since I wrote a blog post. For one thing, “normal” work got in the way. As for community contributions – it has been redirected lately to Youtube videos. Usually it takes less time to record a video than it is to write a post. But posts allow for more details and nuances…

One of my pet peeves is the Mandelbrot Set – it keeps fascinating me, which led me to write a Mandelbrot viewer of sorts for some technologies/languages I am familiar with (C++, C++ AMP, C#/WPF, C#/UWP, …). I recently realized I failed to do so with Rust, my favorite language these days. This post will attempt to right that wrong.

This post assumes the reader has a basic understanding of Rust, although I’ll try to explain anything that looks complicated.

Creating a New Project

Creating a new project for the Mandelbrot Set is no different than any other Rust project:

cargo new mandelbrotThen we go into the newly created mandelbrot directory and start some IDE from there. The most common (probably) IDE Rust devs use is Visual Studio Code with the rust-analyzer extension that does much of the heavy lifting. This works well enough, but recently I decided to switch to JetBrains RustRover, which is dedicated to Rust, and is not generic like VSCode. RustRover is free for personal use, and I prefer it over VSCode, but YMMV.

Open the directory with VSCode, RustRover, or any other IDE/editor you prefer.

Building the Mandelbrot Set

Building the Mandelbrot Set itself has little to with how its represented, so we can start with that. We need support for complex numbers, so we’ll add the num-complex crate to cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

num-complex = "0.4.6"

We’re going to work with f64 types for the complex numbers, so we can define a simpler type going forward (in main.rs):

type Complex = num_complex::Complex<f64>;

We’ll write a function that has a loop for a given iterations, and a point to check whether it belongs to the set or not, and it will return a loop index as soon as the point is determined not to be part of the set. If after all iterations, it seems it is part of the set, then the number of iterations is returned (which is the highest). This could look like this:

fn mandelbrot_color(c: &Complex, upper: u32) -> u32 {

let mut z = Complex::ZERO;

for i in 0..=upper {

z = z * z + c;

if z.norm_sqr() > 4.0 {

return i

}

}

upper

}

(Unfortunately, this WordPress client has no syntax highlighting support for Rust, so I chose C++ as the next best thing. Shame!)

The function is somewhat misnamed, as it’s not returning any color – it’s returning an index, which can be used to represent a color, as we shall see.

The function takes a Complex number and an upper limit for iterations. The Mandelbrot sequence is calculated (z multiplied by itself, added to c, becoming the new z). If its magnitude squared is greater than 4, it’s diverging, so it’s not part of the set. Its “speed” of divergence is indicated by the returned value.

At some point, we must decide how to represent the pixels we’ll eventually display. One obvious choice is a matrix of pixels, each 32-bit in size, comprising of a Red, Green, Blue, and Alpha components, each with a value between 0 and 255. Let’s go with that.

mandelbrot_color works on a single point, so we need to iterate over a matrix of pixels, and the range in the complex plane where the points to calculate reside. The function named mandelbrot is responsible for that. It takes the aforementioned parameters and in addition it takes the matrix data to modify:

fn mandelbrot(data: &mut [[u8; 4]], from: &Complex, to: &Complex, width: u32, height: u32) {

for y in 0..height {

for x in 0..width {

let c = Complex::new(

from.re + (to.re - from.re) * x as f64 / width as f64,

from.im + (to.im - from.im) * y as f64 / height as f64,

);

let iter = mandelbrot_color(&c, 255);

let index = (y * width + x) as usize;

data[index] = [ 255 - iter as u8, 255 - iter as u8, 255 - iter as u8, 255];

}

}

}

The first parameter type looks complex (no pun intended), but it’s a mutable reference to a slice to an array of 4-bytes. Of course, we must ensure that the number of elements in the slice is correct, otherwise the program will panic if we go beyond the slice size. The other parameters consist of the “top left” and “bottom right” corners of the complex plane to go over, and the width and height representing the number of pixels we have to work with.

Next, we start a 2D loop that goes over all pixels. For each one, it calculates the value of c by linearly interpolating in the x and y dimensions (or real and imaginary if you prefer). Then the call is made to mandelbrot_color with the value of the point calculated (c) and an upper limit of 255. This is makes it easy to use the return value directly as a color component. In this first attempt, the code just set the value directly to the RGB components, making it a shade of gray. The alpha component is set to 255, so the color is opaque. The pixel index is calculated (index) and the 4-byte array is assigned. Notice how elegant it is – no need for C-style memcpy or something like that. The actual color values are inverted, so that if the point belongs to the set it’s black, and if it “runs away” quickly, it gravitates towards white. Of course, the reverse would also work, but the “classic” selection is to have points in the set in black.

Drawing the Set

It’s time to show something on the screen. How would we plot all the pixels with their (grayscale for now) colors? I could do something Windows-specific, maybe some interop with the Windows GDI and such. This is certainly possible, but why not take advantage of the cross-platform nature of Rust. There are many crates that can do graphics that are cross-platform, supporting at least Windows, Linux and MacOS.

There are many options here, but I decided to go with a (relatively) simple one, a crate called macroquad (which is open source of course). This library can be used to create games, but in this program we’ll use some of the basics needed to display a bitmap. Here is the updated dependencies in cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

macroquad = "0.4.14"

num-complex = "0.4.6"We’ll add a couple of use statements to make coding less verbose:

use macroquad::prelude::*;

use macroquad::miniquad::window;

Here is the general layout of the main function when using macroquad:

#[macroquad::main("Mandelbrot")]

async fn main() {

// init

loop {

// draw, handle input, ...

next_frame().await

}

}

This is certainly an unusual main, even by Rust standards. The main function is async, which normally isn’t allowed (because any call to await needs to return to some runtime, but there is no “returning” from main to anywhere but the OS). To make this compile (and work), macroquad provides a macro (macroquad::main) that provides the “magic”. Going into that in detail is beyond the scope of this post. Rust developers that are familiar with the tokio crate that provides a generic runtime for async/await have seen this pattern – tokio has its own “magical” macro that allows main to be async.

The point of all this is to allow calling next_frame().await that essentially waits for the vertical retrace of the monitor, keeping a steady frequency based on the monitor’s current frequency. That’s all we need to know – this loop runs 60 times per second or whatever the monitor’s frequency happens to be. Our job is to do the drawing and any other logic before “presenting” the next frame. Those familiar with concepts like double-buffering, graphic pipeline, etc. – it’s all there somewhere, but hidden from direct access for simplicty, certainly more than enough for our purposes.

Let’s begin by doing the initialization. We’ll try to keep the code as simple as possible, even if that means certain repetition. The interested reader is welcome to improve the code! Here is the first part of the initialization:

let (mut width, mut height) = window::screen_size();

let mut from = Complex::new(-1.7, -1.3);

let mut to = Complex::new(1.0, 1.3);

let mut image = Image::gen_image_color(width as u16, height as u16, BLACK);

let mut bmp = Texture2D::from_image(&image);

We start by defining width and height that hold the current window size. The window struct is provided by macroquad. Part of its simplicity is that there is just one window, so the “methods” on window are associated functions (“static” functions for you C++/C#/Java people). screen_size, despite the name, returns the window size, which can be changed by the user by dragging in the usual way, so we may need to update these variables, which is why they are declared as mutable.

Next, we initialize from and to to give a good visual of the entire Mandelbrot set. The user will be able to zoom in by selecting a rectangle with the mouse, so there variable will change as well.

Now we need that array of pixels – the Image struct (from macroquad) manages such a buffer – we create it with the get_image_color helper that fills everything with black (BLACK is a const color provided by macroquad, and is imported by the use macroquad::prelude::*. Lastly, we need an actual texture that a GPU can draw, so we create one from the bits stored in the image. Both image and bmp are mutable, because of the possibility of window size changes, as we’ll see.

The second part of the initialization consists of activating the mandelbrot function to calculate the initial image, so we have something to show when we enter the loop:

mandelbrot(image.get_image_data_mut(), &from, &to, width as u32, height as u32);

bmp.update(&image);

We call mandelbrot with the current values of from, to, width and height. The only tricky part is getting a mutable reference to the internal array stored in the image object – this is the job of get_image_data_mut. It provides the exact [[u8;4]] required by mandelbrot. The texture’s update method takes in the updated pixels.

There a few more initializations we’ll need, we’ll these later. Now, we can enter the loop, and at the very least draw the current state of the texture:

loop {

let params = DrawTextureParams {

dest_size: Some(Vec2::new(width,height)),

..Default::default()

};

draw_texture_ex(&bmp, 0.0, 0.0, WHITE, params);

next_frame().await

}

Normally, we could call draw_texture to draw the texture, and that would work well before the user resize the window. However, if the window is resized, the texture would either not fill the entire window or be cut off. To deal with that, we can use the extended version that requires a DrawTextureParams struct, that has some customization options, one of which is the destination size (dest_size) that we set to the current width and height. You may be wondering what is the strange syntax with that “default” stuff. In Rust, creating a struct instance (object) manually (that is, with no “constructor” associated function to help) requires initializing all members. This is what the structure looks like (press F12 in VSCode ot RustRover to navigate to the definition):

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct DrawTextureParams {

pub dest_size: Option<Vec2>,

pub source: Option<Rect>,

pub rotation: f32,

pub flip_x: bool,

pub flip_y: bool,

pub pivot: Option<Vec2>,

}

I have removed the comments that describe each member so we can focus on the essentials. The idea is that we want to change dest_size but take all the other members with their defaults. But how do we know what these defaults are? We can guess from the documentation/comments, but it would be nicer if we could get all defaults except what we care about. This is exactly what ..Default::default() means. To be more precise, this compiles because DrawTextureParams implements the Default trait (interface):

impl Default for DrawTextureParams {

fn default() -> DrawTextureParams {

DrawTextureParams {

dest_size: None,

source: None,

rotation: 0.,

pivot: None,

flip_x: false,

flip_y: false,

}

}

}

This is pretty much standard Rust – structs can implement this trait to make it easy to work with members directly, but still be able to use default values.

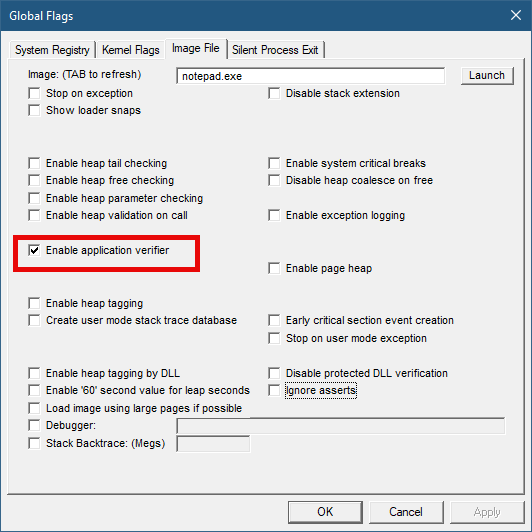

Back to draw_texture_ex: it accepts the texture to draw (on the window), the coordinates to start at (0,0), a tint color (white means no tint, try it with other values like RED or BLUE), and the last argument is our modified params. Running the application as is should show something like this:

Handling Input

So far, so good. The next step is to allow the user to drag a rectangular area to zoom into. For that we need to capture mouse input, and draw a thin rectangle. We can track whether the left mouse button is being held with a simple boolean (selecting), initialized to false in the initialization part.

For mouse input, we get convenient functions from macroquad. First, a mouse down check:

if !selecting && is_mouse_button_down(MouseButton::Left) {

selecting = true;

tl = Vec2::from(mouse_position());

}

If the left mouse button is down, we flip selecting and set the initial point (beginning of the drag operation) in a variable named tl (“top left”), which is of type Vec2 (provided by macroquad), which is a simple (x,y) holder. If the left mouse button is released, we need to zoom into that rectangle by calculating the new from and to and activating mandelbrot:

else if selecting && is_mouse_button_released(MouseButton::Left) {

selecting = false;

let br = Vec2::from(mouse_position());

let size = to - from;

from = Complex::new(

from.re + tl.x as f64 * size.re / width as f64,

from.im + tl.y as f64 * size.im / height as f64,

);

to = Complex::new(

from.re + size.im * (br.x - tl.x) as f64 / width as f64,

from.im + size.im * (br.y - tl.y) as f64 / height as f64,

);

mandelbrot(image.get_image_data_mut(), &from, &to, width as u32, height as u32);

bmp.update(&image);

}

The required calculations are not complex (pun intended), middle-school level math. br (“bottom right”) keeps track of the current mouse position. Then we call mandelbrot and update the texture.

To show the selection rectangle while the user is dragging, we can draw it every frame in a natural way:

if selecting {

let br = Vec2::from(mouse_position());

draw_rectangle_lines(tl.x, tl.y, br.x - tl.x, br.y - tl.y, 2.0, RED);

}

The draw_rectangle_lines is used to draw a non-filled rectangle (draw_rectangle always fills it), which a thickness of 2.0 and a red color.

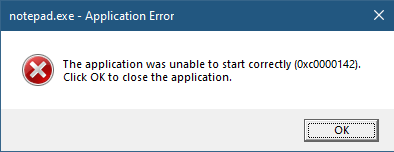

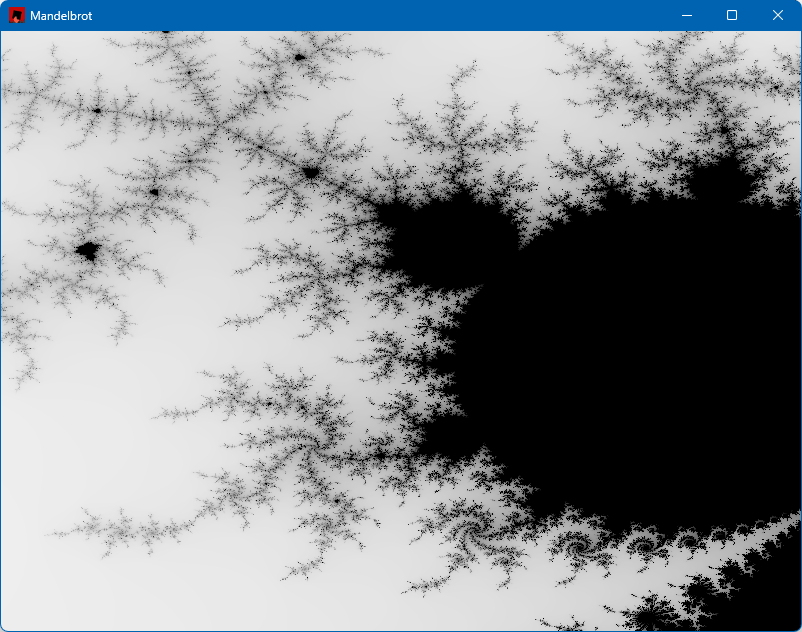

With this code in place, we can zoom in, here are a couple of examples:

Finishing Touches

We still don’t handle window resize. We can use a simple boolean to keep track of resize happening in a frame (size_changed). We can test in the loop if the size has changed:

let size = window::screen_size();

if size != (width as f32, height as f32) {

// new window size

size_changed = true;

}

(width, height) = window::screen_size();

width and height are updated with the current size regardless, so that the texture is drawn correctly. But we also want the image to match the window size. We do that inside the check for a left mouse release where we need to call mandelbrot again so we may as well update the texture appropriately:

if size_changed {

image = Image::gen_image_color(width as u16, height as u16, BLACK);

bmp = Texture2D::from_image(&image);

size_changed = false;

}

mandelbrot(image.get_image_data_mut(), &from, &to, width as u32, height as u32);

bmp.update(&image);

The last two lines have not changed. The image is rebuilt if a new window size is selected.

Lastly, we need some way to reset the set to its original coordinates, if we want to zoom into other areas in the image. We could add a button, but for this example I just added a right-click that resets the values:

if is_mouse_button_pressed(MouseButton::Right) {

from = Complex::new(-1.7, -1.3);

to = Complex::new(1.0, 1.3);

mandelbrot(image.get_image_data_mut(), &from, &to, width as u32, height as u32);

bmp.update(&image);

}

What’s Next?

Are we done? Not really. Two things I’d like to add:

- Make the Mandelbrot calculation faster. Right now it’s a single thread, we can do better.

- Make the image colorful, not just grayscale.

We’ll deal with these items in future posts.

The full code can be found here: