As part of the second edition of Windows Kernel Programming, I’m working on chapter 13 to describe the basics of the Windows Filtering Platform (WFP). The chapter will focus mostly on kernel-mode WFP Callout drivers (it is a kernel programming book after all), but I am also providing a brief introduction to WFP and its user-mode API.

This introduction (with some simplifications) is what this post is about. Enjoy!

The Windows Filtering Platform (WFP) provides flexible ways to control network filtering. It exposes user-mode and kernel-mode APIs, that interact with several layers of the networking stack. Some configuration and control is available directly from user-mode, without requiring any kernel-mode code (although it does require administrator-level access). WFP replaces older network filtering technologies, such as Transport Driver Interface (TDI) filters some types of NDIS filters.

If examining network packets (and even modification) is required, a kernel-mode Callout driver can be written, which is what we’ll be concerned with in this chapter. We’ll begin with an overview of the main pieces of WFP, look at some user-mode code examples for configuring filters before diving into building simple Callout drivers that allows fine-grained control over network packets.

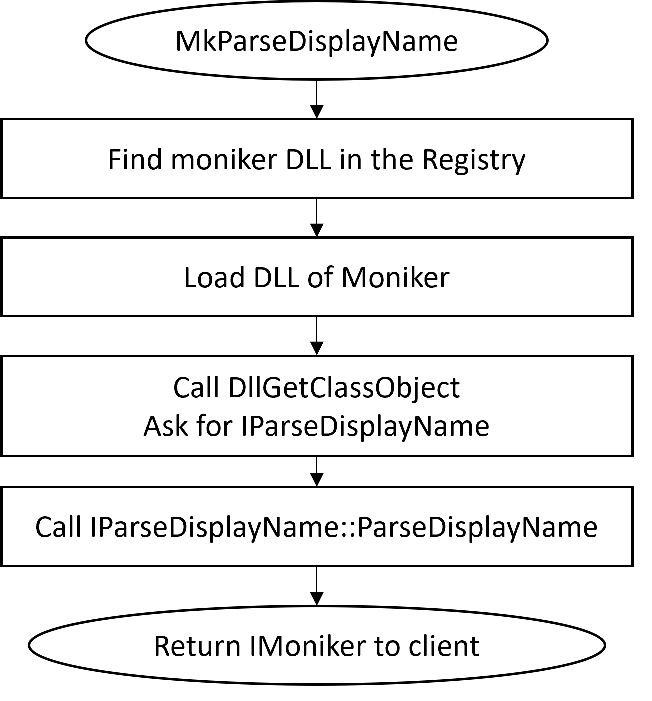

WFP is comprised of user-mode and kernel-mode components. A very high-level architecture is shown here:

In user-mode, the WFP manager is the Base Filtering Engine (BFE), which is a service implemented by bfe.dll and hosted in a standard svchost.exe instance. It implements the WFP user-mode API, essentially managing the platform, talking to its kernel counterpart when needed. We’ll examine some of these APIs in the next section.

User-mode applications, services and other components can utilize this user-mode management API to examine WFP objects state, and make changes, such as adding or deleting filters. A classic example of such “user” is the Windows Firewall, which is normally controllable by leveraging the Microsoft Management Console (MMC) that is provided for this purpose, but using these APIs from other applications is just as effective.

The kernel-mode filter engine exposes various logical layers, where filters (and callouts) can be attached. Layers represent locations in the network processing of one or more packets. The TCP/IP driver makes calls to the WFP kernel engine so that it can decide which filters (if any) should be “invoked”.

For filters, this means checking the conditions set by the filter against the current request. If the conditions are satisfied, the filter’s action is applied. Common actions include blocking a request from being further processed, allowing the request to continue without further processing in this layer, continuing to the next filter in this layer (if any), and invoking a callout driver. Callouts can perform any kind of processing, such as examining and even modifying packet data.

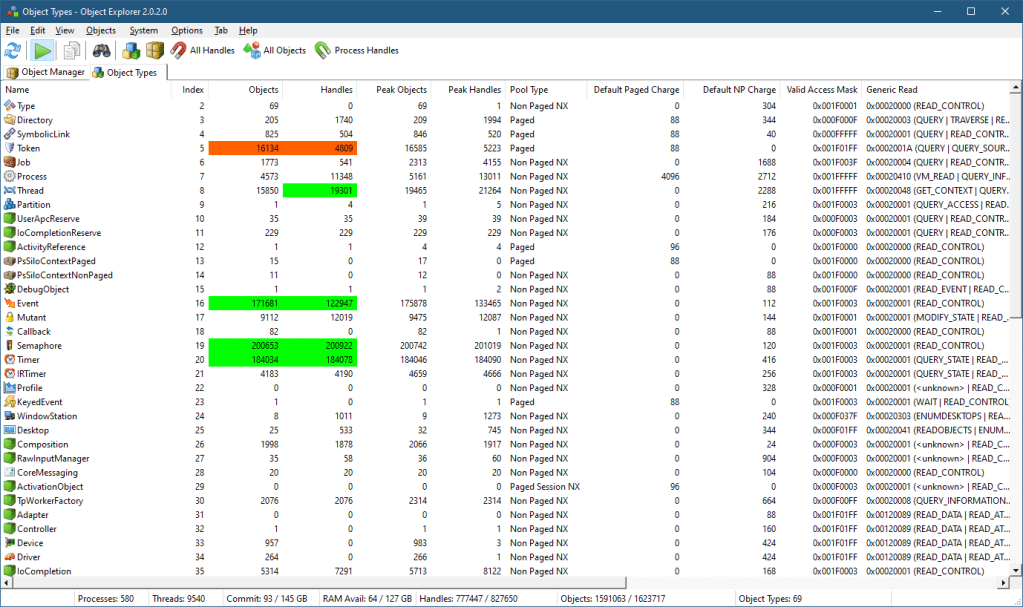

The relationship between layers, filters, and callouts is shown here:

As you can see the diagram, each layer can have zero or more filters, and zero or more callouts. The number and meaning of the layers is fixed and provided out of the box by Windows. On most system, there are about 100 layers. Many of the layers are sets of pairs, where one is for IPv4 and the other (identical in purpose) is for IPv6.

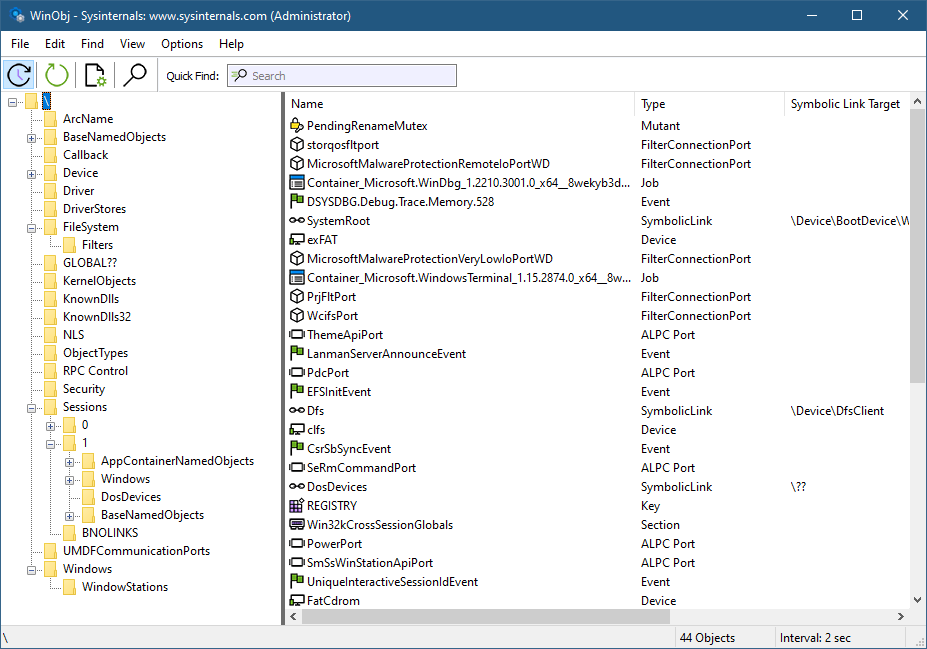

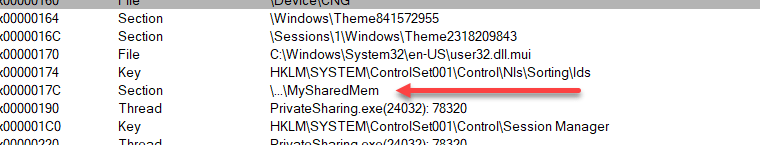

The WFP Explorer tool I created provides some insight into what makes up WFP. Running the tool and selecting View/Layers from the menu (or clicking the Layers tool bar button) shows a view of all existing layers.

You can download the WFP Explorer tool from its Github repository

(https://github.com/zodiacon/WFPExplorer) or the AllTools repository

(https://github.com/zodiacon/AllTools).

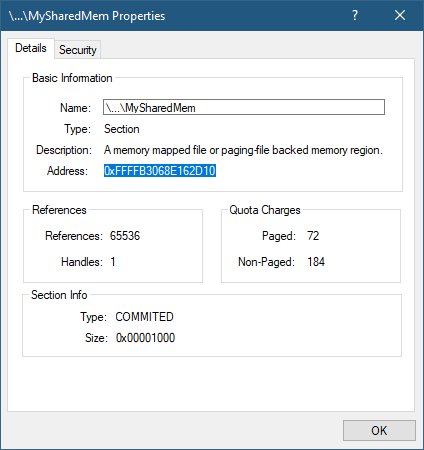

Each layer is uniquely identified by a GUID. Its Layer ID is used internally by the kernel engine as an identifier rather than the GUID, as it’s smaller and so is faster (layer IDs are 16-bit only). Most layers have fields that can be used by filters to set conditions for invoking their actions. Double-clicking a layer shows its properties. The next figure shows the general properties of an example layer. Notice it has 382 filters and 2 callouts attached to it.

Clicking the Fields tab shows the fields available in this layer, that can be used by filters to set conditions.

The meaning of the various layers, and the meaning of the fields for the layers are all documented in the official WFP documentation.

The currently existing filters can be viewed in WFP Explorer by selecting Filters from the View menu. Layers cannot be added or removed, but filters can. Management code (user or kernel) can add and/or remove filters dynamically while the system is running. You can see that on the system the tool is running on there are currently 2978 filters.

Each filter is uniquely identified by a GUID, and just like layers has a “shorter” id (64-bit) that is used by the kernel engine to more quickly compare filter IDs when needed. Since multiple filters can be assigned to the same layer, some kind of ordering must be used when assessing filters. This is where the filter’s weight comes into play. A weight is a 64-bit value that is used to sort filters by priority. As you can see in figure 13-7, there are two weight properties – weight and effective weight. Weight is what is specified when adding the filter, but effective weight is the actual one used. There are three possible values to set for weight:

- A value between 0 and 15 is interpreted by WFP as a weight index, which simply means that the effective weight is going to start with 4 bits having the specified weight value and generate the other 60 bit. For example, if the weight is set to 5, then the effective weight is going to be between

0x5000000000000000and0x5FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF. - An empty value tells WFP to generate an effective weight somewhere in the 64-bit range.

- A value above 15 is taken as is to become the effective weight.

What is an “empty” value? The weight is not really a number, but a FWP_VALUE type can hold all sorts of values, including holding no value at all (empty).

Double-clicking a filter in WFP Explorer shows its general properties:

The Conditions tab shows the conditions this filter is configured with. When all the conditions are met, the action of the filter is going to fire.

The list of fields used by a filter must be a subset of the fields exposed by the layer this filter is attached to. There are six conditions shown in figure 13-9 out of the possible 39 fields supported by this layer (“ALE Receive/Accept v4 Layer”). As you can see, there is a lot of flexibility in specifying conditions for fields – this is evident in the matching enumeration, FWPM_MATCH_TYPE:

typedef enum FWP_MATCH_TYPE_ {

FWP_MATCH_EQUAL = 0,

FWP_MATCH_GREATER,

FWP_MATCH_LESS,

FWP_MATCH_GREATER_OR_EQUAL,

FWP_MATCH_LESS_OR_EQUAL,

FWP_MATCH_RANGE,

FWP_MATCH_FLAGS_ALL_SET,

FWP_MATCH_FLAGS_ANY_SET,

FWP_MATCH_FLAGS_NONE_SET,

FWP_MATCH_EQUAL_CASE_INSENSITIVE,

FWP_MATCH_NOT_EQUAL,

FWP_MATCH_PREFIX,

FWP_MATCH_NOT_PREFIX,

FWP_MATCH_TYPE_MAX

} FWP_MATCH_TYPE;

The WFP API exposes its functionality for user-mode and kernel-mode callers. The header files used are different, to cater for differences in API expectations between user-mode and kernel-mode, but APIs in general are identical. For example, kernel APIs return NTSTATUS, whereas user-mode APIs return a simple LONG, that is the error value that is returned normally from GetLastError. Some APIs are provided for kernel-mode only, as they don’t make sense for user mode.

W> The user-mode WFP APIs never set the last error, and always return the error value directly. Zero (ERROR_SUCCESS) means success, while other (positive) values mean failure. Do not call GetLastError when using WFP – just look at the returned value.

WFP functions and structures use a versioning scheme, where function and structure names end with a digit, indicating version. For example, FWPM_LAYER0 is the first version of a structure describing a layer. At the time of writing, this was the only structure for describing a layer. As a counter example, there are several versions of the function beginning with FwpmNetEventEnum: FwpmNetEventEnum0 (for Vista+), FwpmNetEventEnum1 (Windows 7+), FwpmNetEventEnum2 (Windows 8+), FwpmNetEventEnum3 (Windows 10+), FwpmNetEventEnum4 (Windows 10 RS4+), and FwpmNetEventEnum5 (Windows 10 RS5+). This is an extreme example, but there are others with less “versions”. You can use any version that matches the target platform. To make it easier to work with these APIs and structures, a macro is defined with the base name that is expanded to the maximum supported version based on the target compilation platform. Here is part of the declarations for the macro FwpmNetEventEnum:

DWORD FwpmNetEventEnum0(

_In_ HANDLE engineHandle,

_In_ HANDLE enumHandle,

_In_ UINT32 numEntriesRequested,

_Outptr_result_buffer_(*numEntriesReturned) FWPM_NET_EVENT0*** entries,

_Out_ UINT32* numEntriesReturned);

#if (NTDDI_VERSION >= NTDDI_WIN7)

DWORD FwpmNetEventEnum1(

_In_ HANDLE engineHandle,

_In_ HANDLE enumHandle,

_In_ UINT32 numEntriesRequested,

_Outptr_result_buffer_(*numEntriesReturned) FWPM_NET_EVENT1*** entries,

_Out_ UINT32* numEntriesReturned);

#endif // (NTDDI_VERSION >= NTDDI_WIN7)

#if (NTDDI_VERSION >= NTDDI_WIN8)

DWORD FwpmNetEventEnum2(

_In_ HANDLE engineHandle,

_In_ HANDLE enumHandle,

_In_ UINT32 numEntriesRequested,

_Outptr_result_buffer_(*numEntriesReturned) FWPM_NET_EVENT2*** entries,

_Out_ UINT32* numEntriesReturned);

#endif // (NTDDI_VERSION >= NTDDI_WIN8)

You can see that the differences in the functions relate to the structures returned as part of these APIs (FWPM_NET_EVENTx). It’s recommended you use the macros, and only turn to specific versions if there is a compelling reason to do so.

The WFP APIs adhere to strict naming conventions that make it easier to use. All management functions start with Fwpm (Filtering Windows Platform Management), and all management structures start with FWPM. The function names themselves use the pattern <prefix><object type><operation>, such as FwpmFilterAdd and FwpmLayerGetByKey.

It’s curious that the prefixes used for functions, structures, and enums start with FWP rather than the (perhaps) expected WFP. I couldn’t find a compelling reason for this.

WFP header files start with fwp and end with u for user-mode or k for kernel-mode. For example, fwpmu.h holds the management functions for user-mode callers, whereas fwpmk.h is the header for kernel callers. Two common files, fwptypes.h and fwpmtypes.h are used by both user-mode and kernel-mode headers. They are included by the “main” header files.

User-Mode Examples

Before making any calls to specific APIs, a handle to the WFP engine must be opened with FwpmEngineOpen:

DWORD FwpmEngineOpen0(

_In_opt_ const wchar_t* serverName, // must be NULL

_In_ UINT32 authnService, // RPC_C_AUTHN_DEFAULT

_In_opt_ SEC_WINNT_AUTH_IDENTITY_W* authIdentity,

_In_opt_ const FWPM_SESSION0* session,

_Out_ HANDLE* engineHandle);

Most of the arguments have good defaults when NULL is specified. The returned handle must be used with subsequent APIs. Once it’s no longer needed, it must be closed:

DWORD FwpmEngineClose0(_Inout_ HANDLE engineHandle);

Enumerating Objects

What can we do with an engine handle? One thing provided with the management API is enumeration. These are the APIs used by WFP Explorer to enumerate layers, filters, sessions, and other object types in WFP. The following example displays some details for all the filters in the system (error handling omitted for brevity, the project wfpfilters has the full source code):

#include <Windows.h>

#include <fwpmu.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string>

#pragma comment(lib, "Fwpuclnt")

std::wstring GuidToString(GUID const& guid) {

WCHAR sguid[64];

return ::StringFromGUID2(guid, sguid, _countof(sguid)) ? sguid : L"";

}

const char* ActionToString(FWPM_ACTION const& action) {

switch (action.type) {

case FWP_ACTION_BLOCK: return "Block";

case FWP_ACTION_PERMIT: return "Permit";

case FWP_ACTION_CALLOUT_TERMINATING: return "Callout Terminating";

case FWP_ACTION_CALLOUT_INSPECTION: return "Callout Inspection";

case FWP_ACTION_CALLOUT_UNKNOWN: return "Callout Unknown";

case FWP_ACTION_CONTINUE: return "Continue";

case FWP_ACTION_NONE: return "None";

case FWP_ACTION_NONE_NO_MATCH: return "None (No Match)";

}

return "";

}

int main() {

//

// open a handle to the WFP engine

//

HANDLE hEngine;

FwpmEngineOpen(nullptr, RPC_C_AUTHN_DEFAULT, nullptr, nullptr, &hEngine);

//

// create an enumeration handle

//

HANDLE hEnum;

FwpmFilterCreateEnumHandle(hEngine, nullptr, &hEnum);

UINT32 count;

FWPM_FILTER** filters;

//

// enumerate filters

//

FwpmFilterEnum(hEngine, hEnum,

8192, // maximum entries,

&filters, // returned result

&count); // how many actually returned

for (UINT32 i = 0; i < count; i++) {

auto f = filters[i];

printf("%ws Name: %-40ws Id: 0x%016llX Conditions: %2u Action: %s\n",

GuidToString(f->filterKey).c_str(),

f->displayData.name,

f->filterId,

f->numFilterConditions,

ActionToString(f->action));

}

//

// free memory allocated by FwpmFilterEnum

//

FwpmFreeMemory((void**)&filters);

//

// close enumeration handle

//

FwpmFilterDestroyEnumHandle(hEngine, hEnum);

//

// close engine handle

//

FwpmEngineClose(hEngine);

return 0;

}

The enumeration pattern repeat itself with all other WFP object types (layers, callouts, sessions, etc.).

Adding Filters

Let’s see if we can add a filter to perform some useful function. Suppose we want to prevent network access from some process. We can add a filter at an appropriate layer to make it happen. Adding a filter is a matter of calling FwpmFilterAdd:

DWORD FwpmFilterAdd0(

_In_ HANDLE engineHandle,

_In_ const FWPM_FILTER0* filter,

_In_opt_ PSECURITY_DESCRIPTOR sd,

_Out_opt_ UINT64* id);

The main work is to fill a FWPM_FILTER structure defined like so:

typedef struct FWPM_FILTER0_ {

GUID filterKey;

FWPM_DISPLAY_DATA0 displayData;

UINT32 flags;

/* [unique] */ GUID *providerKey;

FWP_BYTE_BLOB providerData;

GUID layerKey;

GUID subLayerKey;

FWP_VALUE0 weight;

UINT32 numFilterConditions;

/* [unique][size_is] */ FWPM_FILTER_CONDITION0 *filterCondition;

FWPM_ACTION0 action;

/* [switch_is] */ /* [switch_type] */ union

{

/* [case()] */ UINT64 rawContext;

/* [case()] */ GUID providerContextKey;

} ;

/* [unique] */ GUID *reserved;

UINT64 filterId;

FWP_VALUE0 effectiveWeight;

} FWPM_FILTER0;

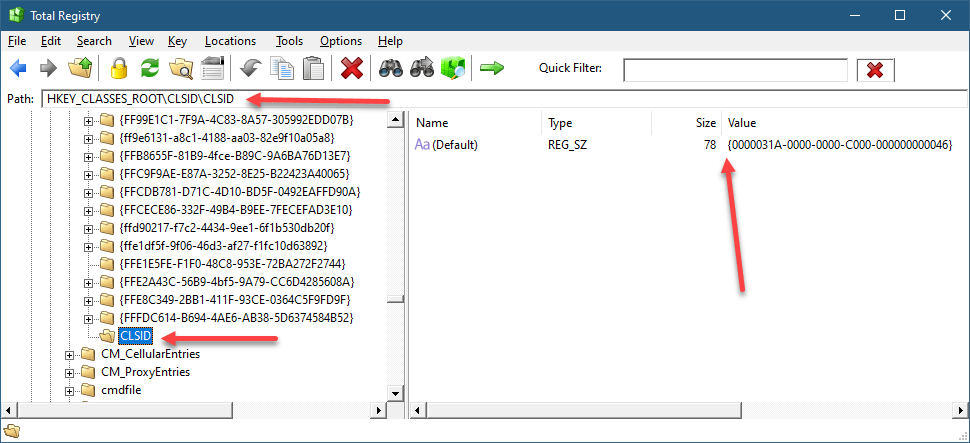

The weird-looking comments are generated by the Microsoft Interface Definition Language (MIDL) compiler when generating the header file from an IDL file. Although IDL is most commonly used by Component Object Model (COM) to define interfaces and types, WFP uses IDL to define its APIs, even though no COM interfaces are used; just plain C functions. The original IDL files are provided with the SDK, and they are worth checking out, since they may contain developer comments that are not “transferred” to the resulting header files.

Some members in FWPM_FILTER are necessary – layerKey to indicate the layer to attach this filter, any conditions needed to trigger the filter (numFilterConditions and the filterCondition array), and the action to take if the filter is triggered (action field).

Let’s create some code that prevents the Windows Calculator from accessing the network. You may be wondering why would calculator require network access? No, it’s not contacting Google to ask for the result of 2+2. It’s using the Internet for accessing current exchange rates.

Clicking the Update Rates button causes Calculator to consult the Internet for the updated exchange rate. We’ll add a filter that prevents this.

We’ll start as usual by opening handle to the WFP engine as was done in the previous example. Next, we need to fill the FWPM_FILTER structure. First, a nice display name:

FWPM_FILTER filter{}; // zero out the structure

WCHAR filterName[] = L"Prevent Calculator from accessing the web";

filter.displayData.name = filterName;

The name has no functional part – it just allows easy identification when enumerating filters. Now we need to select the layer. We’ll also specify the action:

filter.layerKey = FWPM_LAYER_ALE_AUTH_CONNECT_V4;

filter.action.type = FWP_ACTION_BLOCK;

There are several layers that could be used for blocking access, with the above layer being good enough to get the job done. Full description of the provided layers, their purpose and when they are used is provided as part of the WFP documentation.

The last part to initialize is the conditions to use. Without conditions, the filter is always going to be invoked, which will block all network access (or just for some processes, based on its effective weight). In our case, we only care about the application – we don’t care about ports or protocols. The layer we selected has several fields, one of with is called ALE App ID (ALE stands for Application Layer Enforcement).

This field can be used to identify an executable. To get that ID, we can use FwpmGetAppIdFromFileName. Here is the code for Calculator’s executable:

WCHAR filename[] = LR"(C:\Program Files\WindowsApps\Microsoft.WindowsCalculator_11.2210.0.0_x64__8wekyb3d8bbwe\CalculatorApp.exe)";

FWP_BYTE_BLOB* appId;

FwpmGetAppIdFromFileName(filename, &appId);

The code uses the path to the Calculator executable on my system – you should change that as needed because Calculator’s version might be different. A quick way to get the executable path is to run Calculator, open Process Explorer, open the resulting process properties, and copy the path from the Image tab.

The R"( and closing parenthesis in the above snippet disable the “escaping” property of backslashes, making it easier to write file paths (C++ 14 feature).

The return value from FwpmGetAppIdFromFileName is a BLOB that needs to be freed eventually with FwpmFreeMemory.

Now we’re ready to specify the one and only condition:

FWPM_FILTER_CONDITION cond;

cond.fieldKey = FWPM_CONDITION_ALE_APP_ID; // field

cond.matchType = FWP_MATCH_EQUAL;

cond.conditionValue.type = FWP_BYTE_BLOB_TYPE;

cond.conditionValue.byteBlob = appId;

filter.filterCondition = &cond;

filter.numFilterConditions = 1;

The conditionValue member of FWPM_FILTER_CONDITION is a FWP_VALUE, which is a generic way to specify many types of values. It has a type member that indicates the member in a big union that should be used. In our case, the type is a BLOB (FWP_BYTE_BLOB_TYPE) and the actual value should be passed in the byteBlob union member.

The last step is to add the filter, and repeat the exercise for IPv6, as we don’t know how Calculator connects to the currency exchange server (we can find out, but it would be simpler and more robust to just block IPv6 as well):

FwpmFilterAdd(hEngine, &filter, nullptr, nullptr);

filter.layerKey = FWPM_LAYER_ALE_AUTH_CONNECT_V6; // IPv6

FwpmFilterAdd(hEngine, &filter, nullptr, nullptr);

We didn’t specify any GUID for the filter. This causes WFP to generate a GUID. We didn’t specify weight, either. WFP will generate them.

All that’s left now is some cleanup:

FwpmFreeMemory((void**)&appId);

FwpmEngineClose(hEngine);

Running this code (elevated) should and trying to refresh the currency exchange rate with Calculator should fail. Note that there is no need to restart Calculator – the effect is immediate.

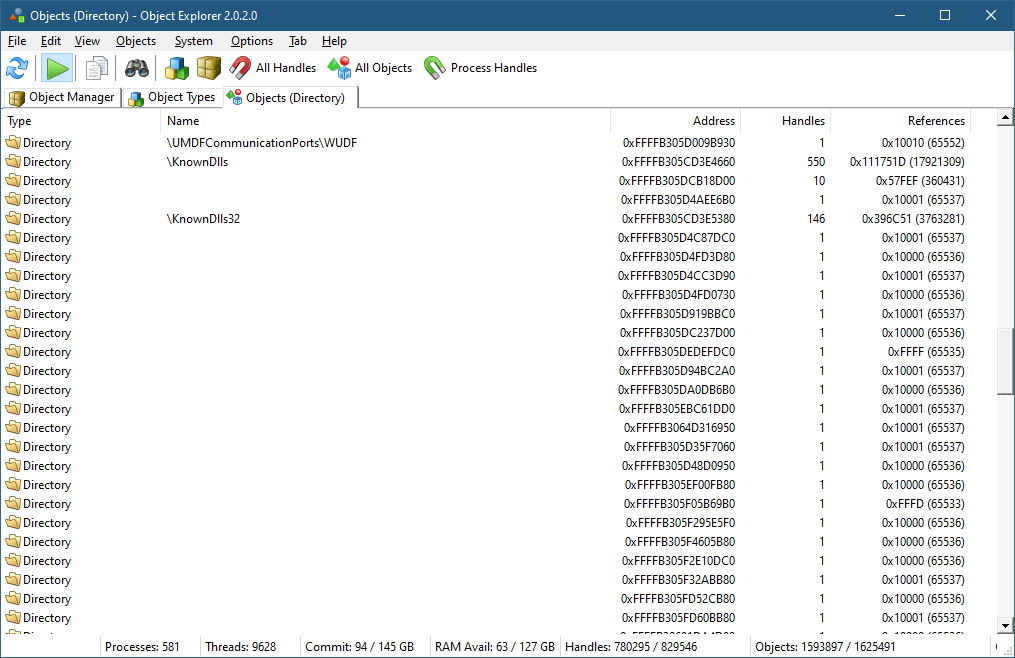

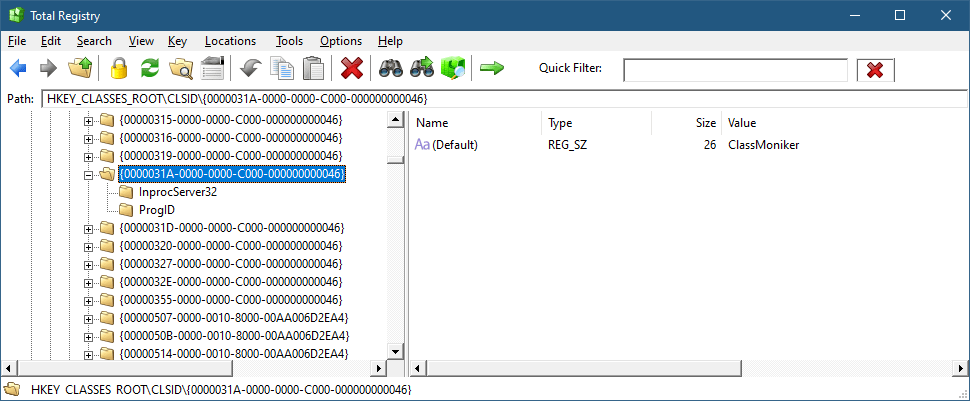

We can locate the filters added with WFP Explorer:

Double-clicking one of the filters and selecting the Conditions tab shows the only condition where the App ID is revealed to be the full path of the executable in device form. Of course, you should not take any dependency on this format, as it may change in the future.

You can right-click the filters and delete them using WFP Explorer. The FwpmFilterDeleteByKey API is used behind the scenes. This will restore Calculator’s exchange rate update functionality.