In part 3 we implemented the bulk of what makes a DataStack – push, pop and clear operations. We noted a few remaining deficiencies that need to be taken care of. Let’s begin.

Object Destruction

A DataStack object is deallocated when the last reference to it removed (typically all handles are closed). Any other cleanup must be done explicitly. The DeleteProcedure member of the OBJECT_TYPE_INITIALIZER is an optional callback we can set to be called just before the structure is freed:

init.DeleteProcedure = OnDataStackDelete;

The callback is simple – it’s called with the object about to be destroyed. We can use the cleanup support from part 3 to free the dynamic state of the stacked items:

void OnDataStackDelete(_In_ PVOID Object) {

auto ds = (DataStack*)Object;

DsClearDataStack(ds);

}

Querying Information

The native API provides many functions starting with NtQueryInformation* with an object type like process, thread, file, etc. We’ll add a similar function for querying information about DataStack objects. A few declarations are in order, mimicking similar declarations used by other query APIs:

typedef struct _DATA_STACK_CONFIGURATION {

ULONG MaxItemSize;

ULONG MaxItemCount;

ULONG_PTR MaxSize;

} DATA_STACK_CONFIGURATION;

typedef enum _DataStackInformationClass {

DataStackItemCount,

DataStackTotalSize,

DataStackConfiguration,

} DataStackInformationClass;

The query API itself mimics all the other Query APIs in the native API:

NTSTATUS NTAPI NtQueryInformationDataStack(

_In_ HANDLE DataStackHandle,

_In_ DataStackInformationClass InformationClass,

_Out_ PVOID Buffer,

_In_ ULONG BufferSize,

_Out_opt_ PULONG ReturnLength);

The implementation (in kernel mode) is not complicated, just verbose. As with other APIs, we’ll start by getting the object itself from the handle, asking for DATA_STACK_QUERY access mask:

NTSTATUS NTAPI NtQueryInformationDataStack(_In_ HANDLE DataStackHandle,

_In_ DataStackInformationClass InformationClass,

_Out_ PVOID Buffer, _In_ ULONG BufferSize,

_Out_opt_ PULONG ReturnLength) {

DataStack* ds;

auto status = ObReferenceObjectByHandleWithTag(DataStackHandle,

DATA_STACK_QUERY, g_DataStackType,

ExGetPreviousMode(), DataStackTag, (PVOID*)&ds, nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

return status;

Next, we check parameters:

// if no buffer provided then ReturnLength must be

// non-NULL and buffer size must be zero

//

if (!ARGUMENT_PRESENT(Buffer) && (!ARGUMENT_PRESENT(ReturnLength) || BufferSize != 0))

return STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER;

//

// if buffer provided, then size must be non-zero

//

if (ARGUMENT_PRESENT(Buffer) && BufferSize == 0)

return STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER;

The rest is pretty standard. Let’s look at one information class:

ULONG len = 0;

switch (InformationClass) {

case DataStackItemCount:

len = sizeof(ULONG); break;

case DataStackTotalSize:

len = sizeof(ULONG_PTR); break;

case DataStackConfiguration:

len = sizeof(DATA_STACK_CONFIGURATION); break;

default:

return STATUS_INVALID_INFO_CLASS;

}

if (BufferSize < len) {

status = STATUS_BUFFER_TOO_SMALL;

}

else {

if (ExGetPreviousMode() != KernelMode) {

__try {

if (ARGUMENT_PRESENT(Buffer))

ProbeForWrite(Buffer, BufferSize, 1);

if (ARGUMENT_PRESENT(ReturnLength))

ProbeForWrite(ReturnLength, sizeof(ULONG), 1);

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER) {

return GetExceptionCode();

}

}

switch (InformationClass) {

case DataStackItemCount:

{

ExAcquireFastMutex(&ds->Lock);

auto count = ds->Count;

ExReleaseFastMutex(&ds->Lock);

if (ExGetPreviousMode() != KernelMode) {

__try {

*(ULONG*)Buffer = count;

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER) {

return GetExceptionCode();

}

}

else {

*(ULONG*)Buffer = count;

}

break;

}

//...

//

// set returned bytes if requested

//

if (ARGUMENT_PRESENT(ReturnLength)) {

if (ExGetPreviousMode() != KernelMode) {

__try {

*ReturnLength = len;

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER) {

return GetExceptionCode();

}

}

else {

*ReturnLength = len;

}

}

ObDereferenceObjectWithTag(ds, DataStackTag);

return status;

You can find the other information classes implemented in the source code in a similar fashion.

To round it up, we’ll add Win32-like APIs that call the native APIs. The Native APIs call the driver in a similar way as the other native API user-mode implementations.

BOOL WINAPI GetDataStackSize(HANDLE hDataStack, ULONG_PTR* pSize) {

auto status = NtQueryInformationDataStack(hDataStack,

DataStackTotalSize, pSize, sizeof(ULONG_PTR), nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

SetLastError(RtlNtStatusToDosError(status));

return NT_SUCCESS(status);

}

BOOL WINAPI GetDataStackItemCount(HANDLE hDataStack, ULONG* pCount) {

auto status = NtQueryInformationDataStack(hDataStack,

DataStackItemCount, pCount, sizeof(ULONG), nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

SetLastError(RtlNtStatusToDosError(status));

return NT_SUCCESS(status);

}

BOOL WINAPI GetDataStackConfig(HANDLE hDataStack, DATA_STACK_CONFIG* pConfig) {

auto status = NtQueryInformationDataStack(hDataStack,

DataStackConfiguration, pConfig,

sizeof(DATA_STACK_CONFIG), nullptr);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

SetLastError(RtlNtStatusToDosError(status));

return NT_SUCCESS(status);

}

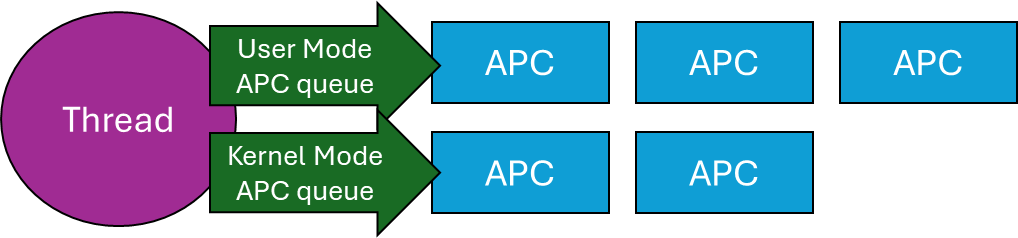

Waitable Objects

Waitable objects, also called Dispatcher objects, maintain a state called Signaled or Non-Signaled, where the meaning of “signaled” depends on the object type. For example, process objects are signaled when terminated. Same for thread objects. Job objects are signaled when all processes in the job terminate. And so on.

Waitable objects can be waited on with WaitForSingleObject / WaitForMultipleObjects and friends in the Windows API, which call native APIs like NtWaitForSingleObject / NtWaitForMultipleObjects, which eventually get to the kernel and call ObWaitForSingleObject / ObWaitForMultipleObjects which finally invoke KeWaitForSingleObject / KeWaitForMultipleObjects (both documented in the WDK).

It would be nice if DataStack objects would be dispatcher objects, where “signaled” would mean the data stack is not empty, and vice-versa. The first thing to do is make sure that the SYNCHRONIZE access mask is valid for the object type. This is the default, so nothing special to do here. GENERIC_READ also adds SYNCHRONIZE for convenience.

In order to be a dispatcher object, the structure managing the object must start with a DISPATCHER_HEADER structure (which is provided by the WDK headers). For example, KPROCESS and KTHREAD start with DISPATCHER_HEADER. Same for all other dispatcher objects – well, almost. If we look at an EJOB (using symbols), we’ll see the following:

kd> dt nt!_EJOB

+0x000 Event : _KEVENT

+0x018 JobLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x028 ProcessListHead : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x038 JobLock : _ERESOURCE

...

The DISPATCHER_HEADER is in the KEVENT. In fact, a KEVENT is just a glorified DISPATCHER_HEADER:

typedef struct _KEVENT {

DISPATCHER_HEADER Header;

} KEVENT, *PKEVENT, *PRKEVENT;

The advantage of using a KEVENT is that the event API is available – this is taken advantage of by the Job implementation. For processes and threads, the work of signaling is done internally by the Process and Thread APIs.

For the DataStack implementation, we’ll take the Job approach, as the scheduler APIs are internal and undocumented. The DataStack now looks like this:

struct DataStack {

KEVENT Event;

LIST_ENTRY Head;

FAST_MUTEX Lock;

ULONG Count;

ULONG MaxItemCount;

ULONG_PTR Size;

ULONG MaxItemSize;

ULONG_PTR MaxSize;

};

In addition, we have to initialize the event as well as the other members:

void DsInitializeDataStack(DataStack* DataStack, ...) {

//...

KeInitializeEvent(&DataStack->Event, NotificationEvent, FALSE);

//...

}

The event is initialized as a Notification Event (Manual Reset in user mode terminology). Why? This is just a choice. We could extend the DataStack creation API to allow choosing Notification (manual reset) vs. Synchronization (auto reset) – I’ll leave that for interested coder.

Next, we need to set or reset the event when appropriate. It starts in the non-signaled state (the FALSE in KeInitializeEvent), since the data stack starts empty. In the implementation of DsPushDataStack we signal the event if the count is incremented from zero to 1:

NTSTATUS DsPushDataStack(DataStack* ds, PVOID Item, ULONG ItemSize) {

//...

if (NT_SUCCESS(status)) {

InsertTailList(&ds->Head, &buffer->Link);

ds->Count++;

ds->Size += ItemSize;

if(ds->Count == 1)

KeSetEvent(&ds->Event, EVENT_INCREMENT, FALSE);

}

//...

In the pop implementation, we clear (reset) the event if the item count drops to zero:

NTSTATUS DsPopDataStack(DataStack* ds, PVOID buffer, ULONG inputSize, ULONG* itemSize) {

//...

memcpy(buffer, item->Data, item->Size);

ds->Count--;

ds->Size -= item->Size;

ExFreePool(item);

if (ds->Count == 0)

KeClearEvent(&ds->Event);

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

//...

These operations are performed under the protection of the fast mutex, of course.

Testing

Here is one way to amend the test application to use WaitForSingleObject:

// wait 5 seconds at most for data to appear

while (WaitForSingleObject(h, 5000) == WAIT_OBJECT_0) {

DWORD size = sizeof(buffer);

if (!PopDataStack(h, buffer, &size) && GetLastError() != ERROR_NO_DATA) {

printf("Error in PopDataStack (%u)\n", GetLastError());

break;

}

//...

DWORD count;

DWORD_PTR total;

if (GetDataStackItemCount(h, &count) && GetDataStackSize(h, &total))

printf("Data stack Item count: %u Size: %zu\n", count, total);

}

Refer to the project source code for the full sample.

Summary

This four-part series demonstrated creating a new kernel object type and using only exported functions to implement it. I hope this sheds more light on certain mechanisms used by the Windows kernel.